Part 2 of a Series

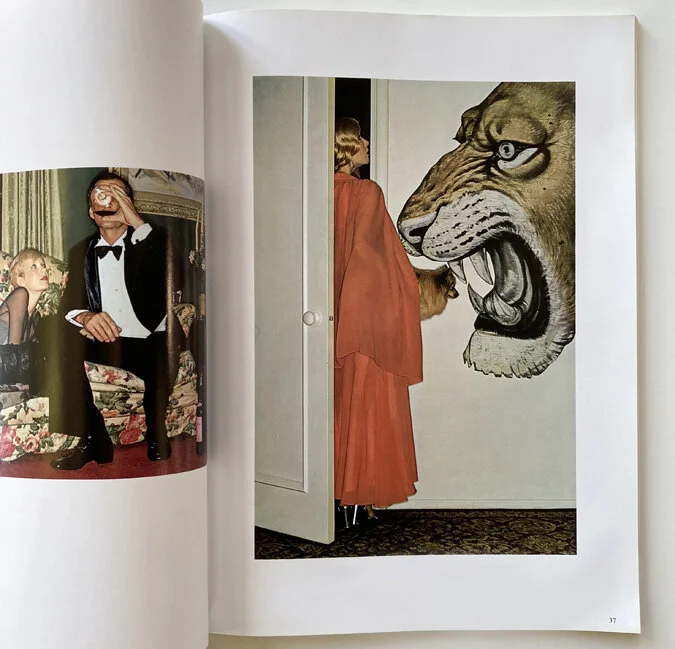

(Right): Pam and Nipper © 1974 Steven Silverstein. All rights reserved. Published in Zoom magazine with interview (1975).

As the Summer of the Pandemic dragged on, I worked on an on-going abstract series, a catharsis for the odd world we’re living in, and continued revisiting images from the beginning of my career.

I dug into my first portfolio that I created in Los Angeles in the 1970s, which eventually became the catalyst for my fashion photography career in Paris. As a young conceptual photographer I came up with ideas and set about creating them, occasionally using trompe l'œil devices, an art form of deception with illusion and humor.

In one of these photos, Pam and Nipper, above right, it appears that Nipper, in the arms of Pam, is about to be nipped by a very large and angry lion. I’m not sure where the perversity of that humor came from but the visual deception provokes a double take, and for dog, lion, and model lovers, full disclosure: no animals or models were harmed for the photo!

During the early pre-Photoshop years until the 1990s, I was occasionally asked to use similar trickery to achieve advertising concepts. These included the illusion of a skier doing flips in Nordica boots in the Alps, and an astonished man looking at a rock band coming out of a VHS box onto the palm of his hand.

Camera degli Sposi: Ceiling Oculus (1474) by Andrea Mantegna. Courtesy: Ministry of Cultural Heritage

Tromp l’oeil dates back to the ancient Greeks and Romans but the Italian painters during the Renaissance really upped the game, attempting to present “reality” through the use of “windows” where the viewer observed scenes. They played with perspective and the depth of space to suggest a receding picture plane into an imaginary three-dimensional world beyond a doorway or curtain, belying the bounds of its actual physical space.

One of the most convincing examples of Renaissance trompe l’oeil is Andrea Mantegna’s Camera degli Sposi: Ceiling Oculus (1474) in the Ducal Palace of Mantua Italy. See above. The entire room is painted with fictive classical architectural details. But most astounding is the oculus, painted di sotto in su (from below to above), which appears open to the sky. As the viewer gazes up from the floor, a ring of winged cherubs and servants peer down, laughing, teasing their audience with spears and a large potted plant teetering on the edge.

In the nineteenth century, some artists took this device of deception literally one step further. Pere Borrell del Caso’s boy in Escaping Criticism (1874) appears to step out of its frame toward the viewer, his eyes wide open in wonderment as if he is seeing the world outside of the painting for the first time.

Escaping Criticism (1874) by Pere Borrell del Caso. Private collection (Bank of Spain, Madrid). Wikipedia Commons.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pablo Picasso invented cubism, a new way of capturing realism using multiple vantage points to create a fractured subject, arguably a form of trompe l’oeil. Picasso’s brother in cubism, Georges Braque, painted similar faceted compositions, and in 1911 as the work became more abstracted and “flat,” he began experimenting with textures and pasting wallpaper onto drawings. This innovative “collage” technique gave way to a new form of trompe l’oeil as the two painters further complicated 2D reality, combining pieces of objects and papers, with painting.

One example of this is Picasso’s Composition with Violin, Fruits and a Glass (1912), below right, which contains newspaper clippings, charcoal drawings, and illustrations, including a violin broken up into different surfaces. It appears to be a cubist homage to Trompe l’oeil with violin, painters implements and self-portrait (1675), below left, by Flemish painter Cornelius Norbertus Gysbrechts, another master of deception.

(Left) Trompe l’oeil with violin, painters implements and self-portrait (1675) by Cornelius Norbertus Gysbrechts. (Right) Composition with Violin, Fruits and a Glass (1912) by Pablo Picasso. Both courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Cubism influenced mid-century abstract art. And, in the 1970s, some abstract artists began experimenting with illusion in their paintings, using elements of perspective and artificial light sources. Eventually that movement fell out of favor as new devices and styles took its place.

I’ve left behind the deception of my early trompe l’oeil long ago. Today, my experimental work creating in-camera photographic abstractions uses a very different process and outcome, as far from realism as possible. But I’m continuing to deploy trompe l’oeil, simultaneously disturbing the “reality” of representational photography by creating abstract imagery with a camera (not with a computer), and toying with the viewer’s perception of the flat picture plane. Is it what it seems?

Composition in Blue and Brown, archival pigment on canvas, 24.5 x 34 inches, Artist Proof, photographic abstraction by Steven Silverstein in situ. @ Steven Silverstein. All rights reserved.

Available framed and ready to hang. Please reach out.